Search This Blog

About FILMS: going, criticism, craft, festivals, etc, by Mr. Whiplash (aka Jack Gattanella).

Posts

Showing posts from October 11, 2015

Spooktacular Savings #13: Guillermo del Toro's CRIMSON PEAK (2015)

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

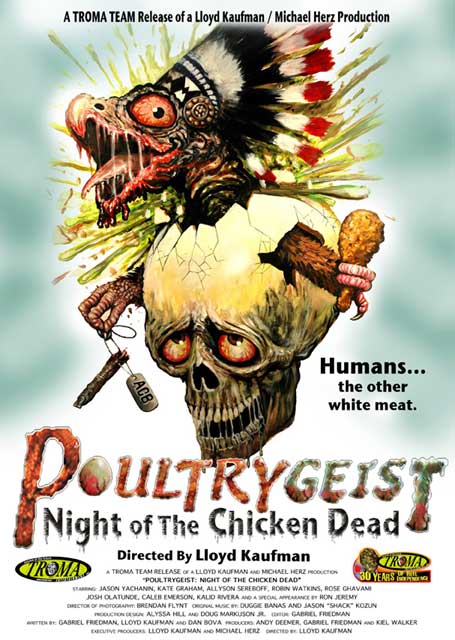

Spooktacular Savings #12: Troma's POULTRYGEIST: NIGHT OF THE CHICKEN DEAD

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Spooktacular Savings #11: LOST SOUL: THE DOOMED JOURNEY OF RICHARD STANLEY'S ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Spooktacular Savings #10: Jack Clayton's THE INNOCENTS (1961)

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps