Netflix-a-thon (#20) Paul Schrader's MISHIMA

The life and work of writer Yukio Mishima, whom I knew little about going into Paul Schrader's 1985 film outside of being a very celebrated and popular novelist in Japan and that he killed himself in 1970, is half enough for a movie, and Schrader knew this. This is why the film, which is broken up as "A Life in Four Chapters", tells not just his life story from awkward stuttering child to rejected-for-war teenager to acclaimed novelist and closet homosexual to his final day on Earth with his comrades, but also that of his works themselves, full of passion and political strife and some hard, sometimes melodramatic choices.

It's an ambitious artistic achievement that has Schrader, co-writing with his brother Leonard, at his full powers with his talents for storytelling and complex character relationships, investigation into what makes an artistic person with concerns about life and death and physical beauty and "duty" to the empire. And with collaboration from many key crew and a composer of some (MAJOR) note it soars. It's sometimes a difficult film, and experimental in how it uses its sets and (fake) locations not to mention color and black and white. And for a serious cinephile interested in bio-pics that veer from the expected and tried-and-true it's an essential

Mishima, which was his pen name, grew up in a household mostly without a mother, or one that mostly (as the film shows) kept him him inside by his grandmother, who in one semi (or just downright) disturbing scene has her rub her legs through a blanket as she badmouths his mother. Then it cuts ahead to life with his brother, as they meet girls and poor young some-day Mishima doesn't know what to do with a girl who is also an adolescent and sexually aware. If you thought the sight of Colin Firth in The King's Speech was awkward from his stammering, this gives that its run of money. He is, in his time spent with other kids on the playground or with his brother, a social mess, and he realizes at one crucial point in the narration we hear how he differentiates the world and words, and also what would be a constant life-thought: how does one become beautiful?

In these early scenes, perhaps it was just from knowing more about the director than the subject at hand, but it felt very personal. Maybe Schrader, despite being from the Mid-West and Calvinist-Dutch upbringing, saw something in Mishima that he would relate to as a big bag of contradictions who had talent but came from a repressive background. I like when a filmmaker is able to tap into something in the subject and it's not an immediately recognizable thing unless one is very aware of the artist's background and possible connection with it, because it allows for personal expression through 'smuggling', if that makes sense. Mishima may be more about Schrader in some respects than it is about the man himself, or what we could ever know about him. It's a tale told of a man's life as he's certain of his abilities, and keeps his darker secrets mostly hidden, and has a view of the world that has beauty and the darkness of death, and when it comes to his artistic sensibility, there's no choice except to write and make films, as Mishima did until he resolved to die himself.

In other words, the film is not easy to peg on a first viewing. Mishima wrote stories that were more easily definable, though still with complex emotional components, and they're recreated here in the film, interspersed with Mishima flashbacks to youth and to his successful days as a writer, traveling the world, seeing how he could "become" beautiful, and becomes politically active at speeches. These recreations of stories are the first exposure I've had to them (all stories and novels, of which he had many, unread by me), but that doesn't matter so much. What does is how they're expressed with all of these sets which are precisely artificial in the colors, how it is in a stage and sometimes constrictive with how much space there is. At first this was unsettling, but I found myself drawn into these sets, sometimes not noticing how staged it was.

The "Runaway Horses" story, about a group of political revolutionaries against Capitalism and who meet a violent fate, was probably my favorite, as it had some of the best acting and the tightest grip on its dramatic structure. But the other stories are intriguing as well, for the romance and freedom with sexuality, and especially how this is all shot. I have to stress this so you know: this film is achingly beautiful in how it's shot by John Bailey, as he and Schrader devise a way to make colors stick out more than in a naturalistic work, and then when it cuts to black and white scenes they're sharply drawn in its characters and settings, timeless really, as if they were shot yesterday or 70 years ago. Even in those few moments where the Mishima stories went into some bizarre little sections (usually to do with, as mentioned, some melodramatic stuff and some violence with lovers scorned and so-on), I was unable to look away from the smallest detail in the cinematography.

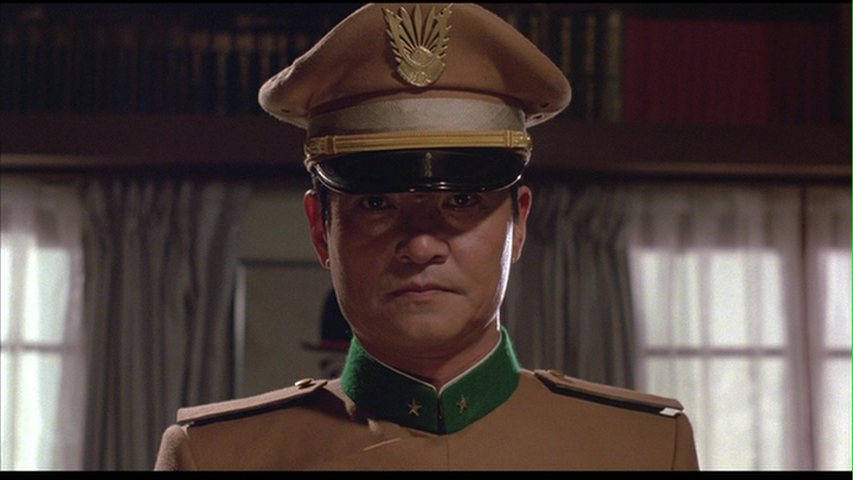

It's surprising somewhat as I almost, kind of, expected something more austere from a director like Schrader, who isn't known for having such lush, vibrant strokes as someone like his contemporary Scorsese. But it's a fever and passion that never stops in the film, mostly attuned to how the characters have this kind of underlying passion underneath some of the formalism of Japanese culture and tradition. This even extends to the sequences with Mishima and his men on the fateful date in 1970 as they drive to their deaths. By turns of how rich and moving Schrader shoots the film and directs his actors, he emphasizes how crucial the point is for Mishima: that his eventual death must have some meaning, and by how he chooses it. In a way the whole movie is about how to choose to die, but also how to live before it, or create stories to live through. It almost has no choice as a film but to be beautiful.

And how can I forget to mention Philip Glass? Good Dog this is among the top-top peaks of his career as a composer. He still plays on the same kinds of orchestral themes he's done throughout his career (surely some may hear some Koyanisquaatsi here), but he has variations, times when he goes into some unexpected places. Like a rock and roll song in one of the stories! There are rare moments here like out of the greatest pieces of cinema where image and music connect so wonderfully. Glass gets maybe more than the director does how important every stroke of strings are in scenes like a young man trying to find a way to cut his belly in Seppuku. It's an intense whole work that compliments or perhaps criticizes as it goes along in a way; as there is a contradiction or unusual angle on screen, Glass' music highlights it, or makes it just a little stranger, or reminds us how achingly human it has to be to be this man, or a character in one of these stylized-artificial stories.

As yet another story that starts off and often stays , as Paul Schrader himself put it, as a "Man in a room" preparing for something and going by any means to execute his plan, it's never less than compelling. He's a character I will enjoy again on a revisit of the film; Mishima is a character who is by turns dead serious, witty and charming, solemn, and with an inner-life that can never let go of the pain of his youth without a ritualistic demise. It is, finally, why I sometimes can affix the term "meditative" on a film and not feel embarrassed for loving it all the same: it meditates on the soul, sex, pain, duty, and honor with maturity, grace, and questioning all the same as he was, at least some of the time, out of his gourd.

(PS: Thank you Criterion for allowing this to be available via Instant-view; I've meant to see this for years, before on DVD and once on a re-release in theaters. It's the only way to go in terms of its remastering for music and image.)

I found it fascinating that the viewer never really gets to know Mishima very well directly. We see these different stages in his life, leading to his suicide, but the treatment is usually cursory and slightly superficial. It's only through the writings that we get a clear picture of who he was and where he was coming from.

ReplyDeleteThat's a good point. I think that was what threw me off at first, how artificial it looked, but it really had a lot to say about Mishima's inner conflicts when it came to relationships and politics and his own self-identity and body.

ReplyDelete