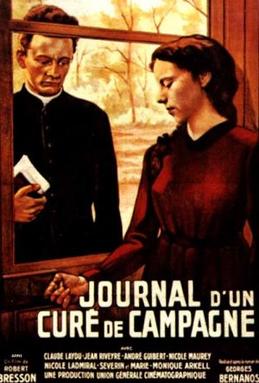

Robert Bresson's DIARY OF A COUNTRY PRIEST

My wife has a term for certain films which carry the weight of importance, and are worth being important, about, but are so heavy as to nearly break ones consciousness. Diary of a Country Priest is that kind of film. It comes out of the gut and heart from director Robert Bresson, and he means it to be a personal cry from its main character, the Priest who becomes a Parish in the French countryside. A film like this one, which takes religion so seriously as to give Ingmar Bergman a run for his spiritual-philosophical money, is loaded with language and thought, though mostly in voice-over. We hear and oftentimes see what this Priest (never given a name, in the credits he's "The Priest of Ambricourt) is thinking and feeling, and more often than not he's in agony. Oh, such pain and agony. He wants to be close to God, and be able to let others feel His Love. Not so easy when it's the countryside and they have more pressing concerns, like doing the menial works they have and trying to live day by day.

There is an unusual amount of scorn for the Priest. Maybe it's because he's so serious about it all, or doesn't look strong enough to really lead people on in any divine way. I think it's more to do with a combination of his disposition, being a sickly, naturally lonely fellow by choice (he is a Priest after all, though even if that profession never existed he'd be celibate anyway), and a Post-WW2 malaise where people become jaded and untrustworthy. And somehow as the film goes along people trust him less and less, or feel close to him. He tires to connect with a middle aged mother who is having such doubts, and their conversation is the centerpiece of the film (at least to me). It's a tense, soulful discussion about faith and what God's Love really means. I'm sure for any person who has questioned faith at one time or another, whatever side you're on, it's a powerful scene that explores how feeling is so much more of a problem in living than thinking when it comes to God and faith, and what hope that may have for a person.

Yes, the film is "Cinematic Oat-Bran" - good for you, and so much to take in (even at two hours) that it makes one weary. Perhaps that's the idea, much like with Bresson's also very depressing Au hasard Balthazar, it is meditative and precise in how it presents characters, realistic but also stylized in how it draws back its human characters from the usual drama. In this film I could tell when a character was angry or emotional not by the loudness of voice but by a certain intensity that is hard to describe except to see it. One big advantage to the film is that while Bresson is using a first-time actor, Claude Laydu, to play the Priest (something Bresson would do his entire career, non-professionals, countless takes, withdrawn, hollow acting), that he is intense and soulful just in the eyes, and how he speaks. The character is weak but hardly inhuman, though everyone else seems not to think so. He only has a few people on his side at all, and those are his superiors; one younger girl could have befriended him, perhaps in an upbringing that wasn't so dismissive and hateful of what someone like the Priest could bring to the Countryside.

I sometimes wasn't clear on why there was so much disdain, but maybe it's not necessary. The strength of the film, and it's a strong one, is how relentless Bresson goes to achieve this sense of spiritual inquiry in the guise of a character study. Yes, there is, at times, a little too much narration in a scene (some of it is interesting in how ordinary it is juxtaposed to an image, other times as a narrative device it falls flat). And its last fifteen minutes are so bleak you'll be careful not to have a razor close-by to do a slicing of the wrists. But the cinematography is simple but demanding in how it moves towards characters or follows them, or how the night is punctuated by the Priest as a lonely figure in the moonlight. And the music is a nice dramatic touch as well, when it comes up it means to amp up the drama where it may be hard to grasp on screen.

Maybe as a "non-believer" I didn't get as much as others might. Frankly it didn't affect me the way a Bergman religious-philosophical film would, though it may be comparing apples from different farms. Diary of a Country Priest, shot in black and white and seemingly done in a timeless frame of existence (though that of a 20th century medium) is essential viewing for serious film "cineastes", though I imagine calling it a "masterpiece" makes it sound like there's work to be done watching it. There is. You do have to meet it halfway. Once you do it gives its stark and haunting rewards, but it's draining too; like the 2006 Paul Greengrass film United 93 I was sucked in to the direction, impressive and groundbreaking as it was in creating its own kind of cinematic language... and then wasn't sure I ever wanted to watch it again.

Comments

Post a Comment